Tourist Photography

Joseph Gleasure

Download this book here!

In the last 12 months, I have had the incredible opportunity to do a tremendous amount of tourism and have feverishly attempted to capture my memories. I have been to Shenzhen, Changsha, Midland en route to Marfa, home to Toronto, and now, almost 24 years to the day after my original trip was planned before cruelly being denied by childhood illness, Tokyo. These trips have provided ample opportunity to practice photography as a skill and an outlet for creative expression. However, the question remains: how should one document and share the output?

Tourist photography is rarely compelling. If we start with the premise that visual art has to be relatable, at least on some level, in some sense, the tourist is already working with a handicap. They are sharing still images of novel experiences with an audience that has not shared this experience and often doesn’t understand what they’re even looking at. After all, few of us are lucky enough to have adoring crowds interested in our lives. Trying to convey the phenomenon of experience is hard, even under ideal conditions. It is made harder when working in a decontextualized setting via digital means such as photography shared online. It is difficult to make strangers care about one’s memories and experiences at the best of times, never mind if these memories are clumsily or amateurishly preserved through digital photography or otherwise. Of course, the audience of these works will mostly be family and friends to whom the photographer can add context to the images via explanation, but we exist during a period of time when families are spread across the continent, if not the globe, making even this simple task impossible. This means that it is imaginary for nearly everyone viewing tourist photography, especially of places we’ve never experienced.

At best, I think a traveler(read: non-professional artist or photographer) can hope for a kind of ‘postcard’ photography that, if not compelling as a piece of visual art, is at least pleasant to look at and technically sound. At this point, what is left within the control of the tourist is some ability to alter the medium in lieu of artistic competency, which is what form the work is presented in, which, of course, has a tremendous impact on how it is perceived and interpreted by otherwise disinterested parties. Previously, I had produced a short video of my time in China and was reasonably pleased with the result. Although the end product did not lend itself particularly well to photography, it made me think about the presentation of photographs in a way I hadn’t done before.

Some Photographic References

Earlier this year, I shared the works of Japanese photographer Takashi Homma with a friend, who noted that Homma was referencing the American Modernist Edward Ruscha with the covers, titles, and subjects of some of his photo books. Homma has long been one of my favourite photographers and is somewhat ubiquitous in contemporary Japanese photography. I know Homma for both his fashion photography and his critically acclaimed landscape photography, which often turns its view on the ‘landscapes’ of Tokyo. Although Homma has historically separated the two styles in his work, my first introduction to Homma was to both subjects simultaneously. In 2001, he was asked to shoot a series of editorials for the apparel brand National Standard. The results were published in fashion magazines as advertisements, where I first saw them, and later compiled into a thin and sadly easy-to-lose book called New Tokyo Standard. The images depicted various eerily still landscapes of Tokyo in bright, vivid colour.

What is most compelling about the images is that amongst the vernacular suburban architecture and corporate parks, which, while drawing clearly from Western influences, remain steadfastly Japanese both in general form and particular details (shrubs are spherical rather than rectangular, fences, signage, streetlamps, facades, building colour and more are all unlike anything you would see in the west even if they’re clearly recognizable as a subject), are that they are almost all empty, both of cars and people. While some images in this series are portraits and obviously have a human subject, and others while landscapes feature some vehicles and some passersby, the images Homma managed to capture so defy expectations of Tokyo as a bustling megalopolis one has to the wonder if what Homma has shot is the same city he says it is.

After this initial foray into Homma’s work, I would go on to find out that he had an earlier book called Tokyo Suburbia from 1998, which has greatly influenced how I view photography as an art form and style. Much like New Tokyo Standard, the book is made up of landscape photos of Tokyo, only this time it is nearly exclusively suburban landscapes that feature in this book, from large (for Japan) single-family homes to newly built apartment complexes on the edge of the sprawling city the book was a landmark in Japanese photography and to reuse the tired cliche, subverted expectations of the exterior city to an international audience much, in the same way, the equally famous Tokyo Style (another landmark in contemporary Japanese photography from the same period as Tokyo Suburbia) by Kyoichi Tsuzuki subverted expectations of what a Tokyo home looks like.

Tsuzuki is an interesting study in photography as he was originally an art critic and translator, being the first to write and translate several volumes of Western art history and monographs for a Japanese audience. Tsuzuki eventually took up the camera himself and began producing his own works, starting with Tokyo Style, a book that depicts the apartments and lives of Tokyo’s citizens as they actually are rather than the idealized preconceptions of ‘zen’ and ‘minimalism’ that westerners impose upon Japanese living. Later books following the same subject matter include: Happy Victims, a hagiographic series of Japan’s hyperconsumption and its ‘victims’. The book, which was originally serialized in the lifestyle magazine Ryuko Tsushin, was a recurring column where Tsuzuki found someone in or around Tokyo who was obsessed with a single fashion brand and then shared their story, their daily routine, name, and occupation alongside a photo of them posing with their collection in their home. Another entry in Tsuzuki’s series of books depicting the interior lives of the Japanese was Universe for Rent Vol. 1 and 2, an expanded version of Tokyo Style, including the homes of people from Kyoto and Osaka. By his own admission, Tsuzuki is not a great photographer from a technical perspective. However, he has leaned into this constraint, and his amateur style of photography lends a candid and observational quality to his works.

While Tsuzuki embraced his technical limitations to create an authentic documentary style, my earlier introduction to Ruscha through Homma's work offered a different approach to photographing the built environment. Having never heard of Ruscha before my friend mentioned the connection between Homma and Ruscha, I explored his work and, at the same friend's urging, developed an interest in American Modernism in general. My primary introduction to Ruscha was through his series of 'various small books' as this was the series that Homma had so faithfully paid homage to.

Much like Tsuzuki, Ruscha was not a 'natural' photographer; however, while Tsuzuki used photos as content and the works were impressive in their own right as photos, what Ruscha attempted to do was eschew photography altogether as his interests lay elsewhere in the production of his books. Starting in 1963, Ruscha began producing his series of photo books despite not being a trained photographer. However, like Tsuzuki, this constraint wasn't an issue as Ruscha was less concerned with the medium of photography and was more interested in creating and proliferating a mass-produced good and simply used photography to fill the books with content rather than as content. This, combined with his predilection for single words or phrases that litter his oeuvre, resulted in a number of books on totally banal subjects with names like 'Twenty Six Gasoline Stations' or 'Some Los Angeles Apartments'.

Ruscha’s books almost all featured a plain white cover with at most three lines of text set in Monotype’s Stymie Extrabold. The leading was then set so that the lines were equidistant from each other and that the top of the letters in the first line touched the top margin of the page while the bottom of the last line touched the bottom margin. Additional changes are made to the tracking and font size of individual lines so that the words come as close to touching the side margins of the page as possible. Usually, if there are changes to the font size, then two lines are the same size, and one single line is modified rather than having all three lines in different sizes. The resulting effect is an implied rectangle on the page's cover that makes great use of the negative space.

The works of these three photographers - Homma, Tsuzuki, and Ruscha - while distinct in their approaches, all share a common thread in their ability to transform ordinary subjects through careful consideration of both content and presentation. Homma's quiet landscapes, Tsuzuki's candid documentation, and Ruscha's systematic cataloguing of various typologies each demonstrate how the photobook format can elevate everyday observations into compelling artistic statements. Their different approaches to both photography and book design provided a framework for considering how to present tourist photography in a way that might transcend its amateur origins. Even if one lacks technical ability, the ability to think, conceive, and execute an idea has, with the rise of conceptual art, begun to supersede the actual physical work of art.

Producing the Mundane

The ability to elevate everyday mundane things is a theme in all three artists' work. While present in different ways, it has formed a foundational aspect of this work and how I chose to present it. Like Tsuzuki’s initial photographic works, the images are quite amateurish, with some unfortunate crops, framing issues, and so on. Like Homma, they are primarily made up of landscapes, and I have attempted to emulate his compositional style and the deep blacks of his photography. However, this is only a pale imitation as he was shooting on film and me on digital. Then, the overall styling and production of the book is an obvious reference to both Homma and Ruscha. I have used the same typeface, general layout, and, while unique to me, a derivative naming structure from both of their versions of this photo book model.

I deviate in the actual format, the grid layout, and the inclusion of themed chapters rather than constraining myself to a singular subject. The book is a PDF set in an 8.5:11 ratio rather than the ‘small’ format of both Homma’s and Ruscha’s books. This is both a common digital format to accommodate printing on domestic and office machines and the default format in a range of software applications from Microsoft Word to Adobe’s Indesign, meaning that it is a familiar and standard format recognizable to the viewer. Additionally, rather than a physical mass-produced good (although with regard to the original books by Homma and Ruscha, they weren’t meaningfully ‘mass produced’ and instead quite limited runs as far as book printing goes), it is a digital good that is theoretically infinitely replicable and thus transposes the idea of mass production to a level previously unavailable to Ruscha when initially producing these books. The grid layout features a slightly larger margin than the original books and a 7x5 grid with gutters to lay out photos and text. The basic rules for photos are as follows: All images are to be aligned to the top left corner of the grid (0.5” on left-facing pages, 9” on right-facing pages), images with a horizontal aspect ratio are resized until they are one column from the rightmost margin, images that have a vertical aspect ratio, are resized to have two columns from the rightmost margin. In cases where a particular series of photos has an even number of photographs, thus leaving a single image on the final two-page spread, the image is resized until there is one row of space between the bottom margin and the image.

To the best of my knowledge, the originals do not include any captions of the photos or descriptions of where the images were taken until at least the book's ending and, in many cases, not at all, leaving viewers to their imaginations on where and what images are depicting and why they are significant. In the context of tourist photography, this weakens the images' strength as sharing experience is a crucial aspect of such photos. To alleviate this concern while staying to the general format Ruscha laid out, the section titles within the book lend some reference to the media or the general theme of the following sections. I have provided short descriptions of each series in case the names are too cryptic to decipher.

Lynne Takes On Japan

These are portraits of Lynne in various neighborhoods around Tokyo. While Lynne is the best subject a photographer could ask for, she is very protective of her image(rightfully so!) and is often difficult to capture well because of this. Many of these photos are taken from behind or obscure her face to account for this constraint.

A Handful of Small Animals

Documents our day at Ueno Zoo and the ‘small animals’ we saw there. The day was extremely bright with little crowd cover, so these images stray into overexposure more than the others. The final image is of several school groups in front of the main gate. Who also constitute ‘small animals’. As we visited on a weekday, the crowd primarily consisted of tourists, seniors, and thousands of schoolchildren.

Mid Morning in Shinjuku Gyoen and Yoyogi Park

Straightforwardly descriptive. These are images from two of the main central parks in Tokyo. The final two images are from Yoyogi Park. Unfortunately, we ran into rain that day, so it was difficult to capture more images. During our trip, we mostly spent the mornings in museums or gardens before going shopping and exploring in the afternoons. This is because very little is open in Tokyo before 11 am.

Several Small Vehicles

Also straightforwardly descriptive. At some point, I realized three things: 1. Many of the vehicles in Japan are scaled-down versions of North American ones. 2. They often come in novel colours such as teal, purple, or pink. 3. I was taking an awful lot of photos of them.

Old Standard Landscapes

Landscapes in the style of Takashi Homma’s ‘New Tokyo Standard’. These are primarily suburbs or subdivisions that show a wide range of buildings and objects.

Some Views of the Imperial Palace

Our second day was supposed to be in Ginza, but having visited the previous day, we decided we had seen almost everything we needed to see and went to Marunouchi instead. What I didn’t realize is that across from the original Tokyo station (final photo), there are largely unobstructed views of the gates of the Imperial Palace. A massive paved driveway is also part of the Imperial Palace and is prominently featured in these photos.

Two Shrines and a River

Images depicting the Ueno Toshogu Shrine, Otori-jinja Shrine, and Meguro River.

Buildings Against a Blue Sky

As with the vehicles, I noticed that buildings in Japan, while built nearly on top of one another, are ‘smaller’ than North American ones and appear as scaled-down versions of Western structures. The density, texture, and inclusion of public infrastructure like electrical wires created tightly woven compositions punctuated by the clear azure of a late fall sky and became a frequent subject of my photographs.

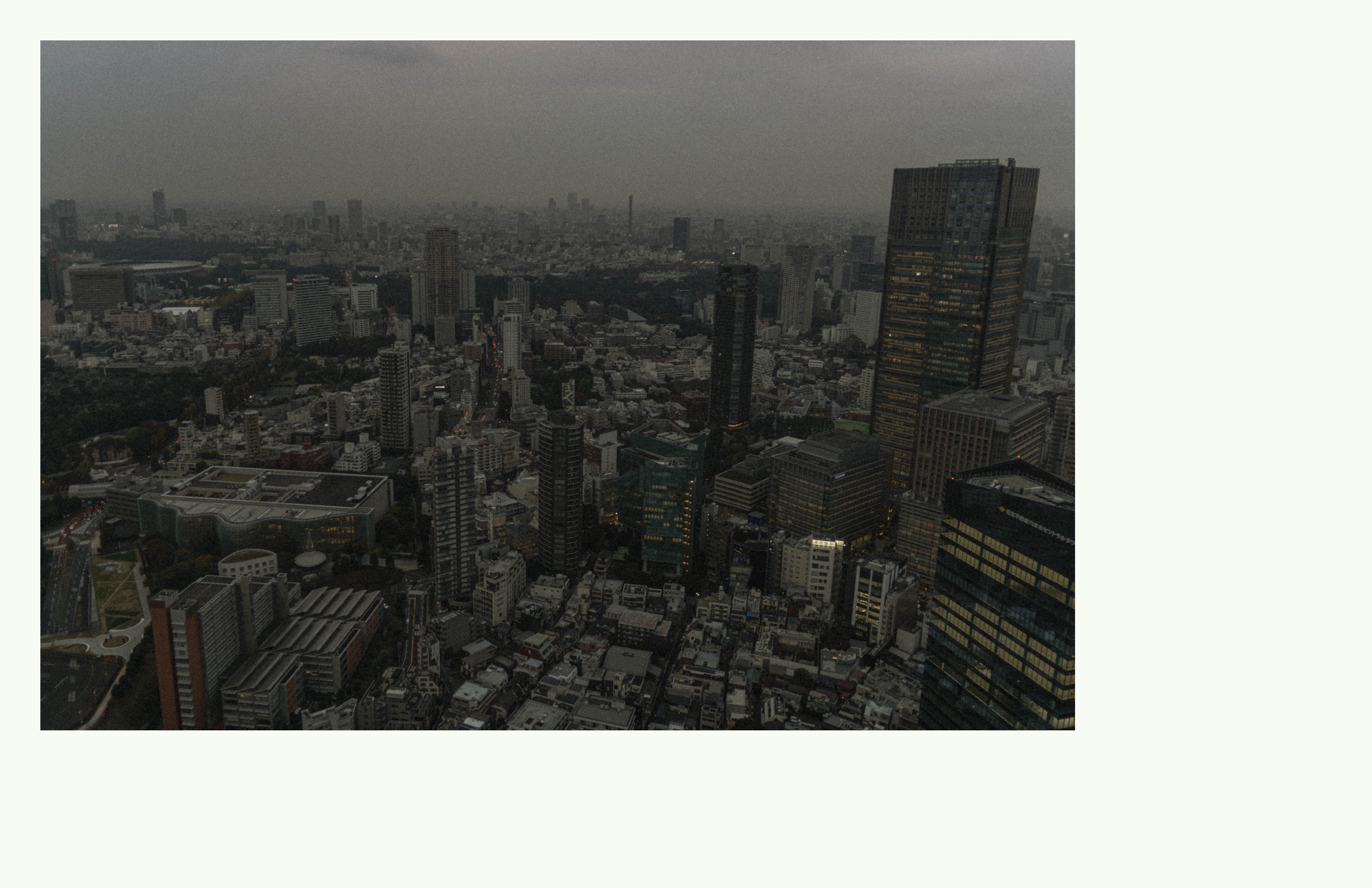

Nite Life

Images of late afternoon and evening in Tokyo. The series title is deliberately stylized as ‘nite’ rather than night to create graphic symmetry. Locations include Nakano and views from the 52nd floor of Roppongi Hills Mori Tower.

New Standard Landscapes

There was a group exhibit called The Gaze of the Present that featured the work of Kanno Sayuri at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum. Sayuri’s contribution, called New Standard Landscapes, documented her local landscape and its changes in the face of rapid development. Similar to Takashi Homma’s photos in subject matter, Sayuri’s images tend to be more cropped and include singular building details as a subject rather than Homma’s broader and more encompassing landscape photos. The photos in this series draw upon that distinction and differ from Old Standard Landscapes by following Sayuri’s lead.

By dividing the photos into common themes, it is possible for a viewer to quickly surmise the aspects and events of Tokyo that I found meaningful and compelling enough to turn my gaze on. I found this aspect of Ruscha’s model beneficial to borrow from. Again, photography was not the main point of his books, and in this case, the photographs are not the thesis of this book either; instead, they are a medium to smooth communication of an experience with an audience in lieu of in-person contact. The audience cannot travel with the photographer, and the photographer cannot assume that the audience is familiar with the subject matter. To prevent communication breakdown or confusion, the photographer can then take proactive steps in designing the medium of the work to aid communication in the face of these latent weaknesses. This, in conjunction with my admiration of photographers like Tsuzuki and Homma and my burgeoning interest in Ruscha’s work, in addition to their relevancy over Japan and architectural landscapes, made these artists a suitable departure point for developing a format to publish my memories. By using a common format and structure (digital photobook disseminated by PDF), providing an additional essay, and refraining from photographic captions, the challenges of tourist photography are met. The original template of the work (Ruscha and Homma’s small books) is respected and maintained with minimal intervention from the photographer, although the interventions made add to the model rather than detract.

The nine series of photos offer a brief but comprehensive view into Lynne’s and my experience during our twelve-day trip to Tokyo in November 2024. My goal with this is to try to bridge the gap of experience and distance that makes sharing photos with family, friends, and strangers so difficult, in spite of our ability for instant communication.